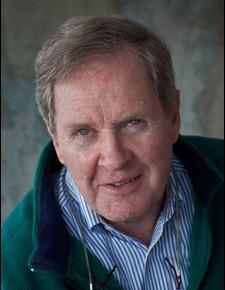

Meet the original Head of the Charles: Dartmouth resident D’Arcy MacMahon

But for Covid, this weekend would have marked the 55th annual Head of the Charles rowing regatta — the largest event of its kind — in Boston.

Luckily, according to Dartmouth resident and regatta co-founder D’Arcy MacMahon, athletes around the globe were still able to participate in the event virtually.

The remote arrangement gives rowers — some of whom hail from as far away as Japan — a chance “to compete on their home body of water,” MacMahon said, adding “I know it means a great deal to thousands of [rowers] to be able stay in touch with the rest of the rowing community, near and far.”

MacMahon remembered overseeing the first-ever Head of the Charles in 1965, along with co-founders Howard McIntyre and Jack Vincent and with help and inspiration from Harvard sculling instructor Ernest Harlett.

“The first year, nobody came to watch the regatta,” he said. “Absolutely nobody.”

He was in charge of writing about the event for a rowing magazine, he noted, so he wrote “Countless thousands lined the shores” in the article as a joke.

“We didn’t count them, because there was nobody,” he laughed. “Most rowers are used to rowing in front of no crowds at all.”

“It’s not a sport that publicizes itself,” he added wryly.

But the next year, he said, to the founders’ amazement — and due largely to the perceived hype — people showed up to watch.

Eventually, as the event and its costs grew, the founders had to get corporate sponsorship.

“We built the regatta into the largest rowing event in the world run entirely with volunteers,” MacMahon said proudly. “So our little regatta, which lost [money] in the first year, now has millions of dollars.”

MacMahon said he enjoyed the early days of the rowing race.

“I liked the regatta when it was mostly for fun, and not taken quite so seriously,” he said, going on to explain, “We took the regatta seriously, but we didn’t take ourselves seriously.”

“The money that’s involved in it now — it’s very different than it was in its embryonic years,” he added.

Since those days, MacMahon has taken a step back from the race.

“I try to stay out of the regatta management’s hair as much as I can,” he laughed. “People don’t want some old fart telling them what they used to do fifty years ago...But for the 50th regatta, they made me come back and row in it.”

MacMahon was born about 100 yards from the river at Mount Auburn Hospital in Cambridge, where he grew up.

He started rowing at the Cambridge Boat Club, which turned into a summer job, and eventually went on to row at high school, college and beyond, earning several accolades — including a win at a regional double sculling championship as well as three races at England’s Henley Royal Regatta — in the process.

“It’s a lifelong sport,” he noted. “You can do it the rest of your life, which is really great.”

MacMahon moved down to the South Coast after marrying his wife, and became the Executive Director of the Lloyd Center for the Environment for years.

“I said I’d do it for a few years and ended up staying for ten,” he laughed.

But his focus eventually returned to rowing.

He now helps run the New Bedford Rowing Center as its executive director, and hopes to get more and more people involved in the sport.

“It’s a great sport for these kids,” he noted. “And unlike tennis or ice hockey, you don’t have to have been doing it since you were four. If you’re slightly athletic and have a good attitude, you’ll be good at it.”

“There’s a place for everybody in rowing,” he said.

As for the Head of the Charles, he noted, although this year his little regatta looks a lot different, “the hurt pales in comparison to what so many are suffering in the world today.”

“I guess we can all just suck it up and devote our energies to things that matter a great deal more, like the harm we are causing to our planet and the economic inequality we see continuing to grow in this country,” he said.

Yet MacMahon said he believes the future looks bright.

“We’ve just gotta keep moving,” he said. “That’s the trick, I think, when you’re getting in your elder years — just to keep moving.”