Buzzards Bay Coalition seeks homeowners to test enviro-friendly septic system

The Buzzards Bay Coalition is currently seeking Dartmouth volunteers to test new septic system technology that could minimize water pollution.

Traditional septic systems contribute to about 70-percent of the Bay’s nitrogen pollution — which can cause fish kills and damage eelgrass habitats, said Korrin Petersen, the Coalition’s senior attorney. “You’ve really depleted the resource that the South Coast have come to depend on.”

The Environmental Protection Agency issued the Coalition a $730,000 grant to install 12 septic systems upgrades across the Buzzards Bay region. The new "layer cake" systems work to filter nitrogen from wastewater.

Now, project staff offering a $10,000 subsidy — which won't cover the entire installation cost — to Dartmouth volunteers who want to update their septic systems to the new "layer cake." Petersen said the goal is to have all 12 systems installed by Fall 2017, followed by three years of testing.

The way nitrogen pollution works:

Traditional septic systems — known as Title 5 systems — remove bacteria and viruses before the wastewater hits groundwater levels and funnels back into the ocean, however these systems do not remove nitrogen.

Nitrogen is a nutrient that encourages plant growth, including algae blooms that either turn the water murky, or form floating mats. During the day, algae flourishes under the sun (photosynthesis), but at night, bacteria starts to break down the plant life, using oxygen from the water to perform that decomposition, said Petersen.

The oxygen levels in the water drop so rapidly that fish can’t breathe nor escape, and massive amounts of them wash up dead on shore — a fish kill. When algae mucks up the water, it inhibits eelgrass from getting sunlight, which it depends on to grow, said Petersen. This damages the eelgrass, which is also a habitat for bay scallops and various fish species.

Background:

Title 5 systems were introduced in 1995 as an upgrade to cesspools. The Title 5 system is typically a 1,500-gallon, concrete tank that collects water from sinks, toilets, showers, and washers and separates the waste. Solids fall to the bottom and are pumped out every 2-3 years; liquids clarify up top and funnel to a leach field, or network of perforated PVC pipes. There is a mandated five-foot clearance between a leach field and ground water level, so that as wastewater empties, bacteria and viruses are filtered out by the sand, explained Petersen.

“There are a lot of us that use Title 5 septic systems,” she said, explaining that the upgrade to the Title 5 only has to be done if owners sell their property or if there’s a system failure. “There’s a lot of cesspools legally in use still.”

The cesspool is just a blocked hole in the ground, said Petersen. There’s no separation; there’s no treatment, and often, it sits in groundwater, she said, which makes the cesspool a major public health concern. Both of these systems feed nitrogen into the water system.

The 'layer cake' system:

The Coalition is working with Barnstable County, water engineering firm Hazen and Sawyer, and the University of Rhode Island to install the "layer cake" systems on properties in Dartmouth, Westport, Acushnet, Carver, Wareham, Falmouth, and Martha’s Vineyard.

The layer cake system was first introduced in Florida for similar reasons: to keep nitrogen out of waterways. Researchers found that the technology removed up to 85 percent of nitrogen. Now researchers are trying it on the South Coast, but there are still many questions involved, including if New England weather or different soil types will restrict its effectiveness.

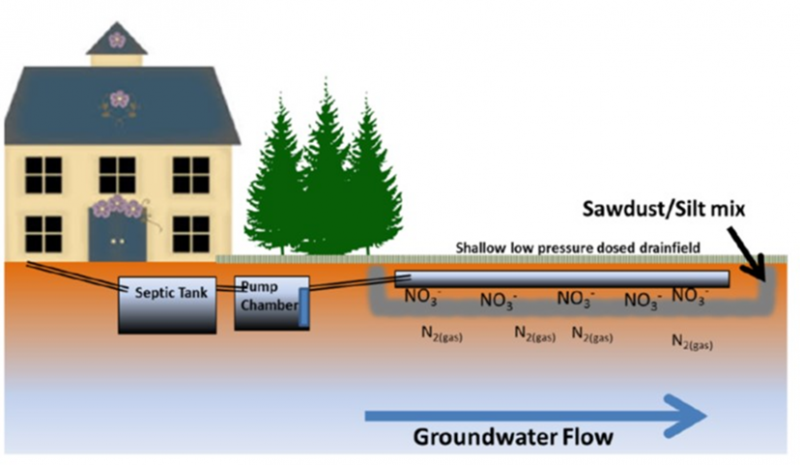

A layer cake system works much like the Title 5. The main difference, however, is that instead of five-feet of sand acting as a filtration, there is 18-inches of sand, and then 18-inches of a sand-sawdust mix, said Petersen.

The layers are part of a two-step process. The sand layer supplies oxygen to bacteria living there, so it can turn nitrogen — typically in the form of ammonia — into a liquid nitrate. Then, oxygen-deprived bacteria in the mixed layer break apart the nitrate to get the oxygen, releasing nitrogen gas as a byproduct. In this way, most of the nitrogen never makes it into the groundwater.

“The layer cake is about creating the proper environment for these bacteria to function,” said Petersen.

Petersen explained that denitrification systems — ones that remove nitrogen gas like the layer cake — do exist, but that the process happens in a system of tanks and pumps instead of in a leach field. These alternatives can be pricey.

“Homeowners don’t want a lot of complicating factors in their septic system,” said Petersen. “It’s about finding the simplest and most affordable way to denitrify their waste water.”

Interested Dartmouth residents who don't currently have a denitrification system can contact Petersen via email (petersen@savebuzzardsbay.org) or by phone (508-999-6363 x206). South Coast natives who aren't ready to upgrade can still help curtail nitrogen pollution by eliminating lawn fertilizer.