Dartmouth treatment centers, police at front line of opioid battle

Story Location

United States

One in ten Americans knows someone who has died from an opioid overdose.

47,600 Americans died from an opioid overdose in 2017 — more than the number of Americans killed in combat during the entire Vietnam War.

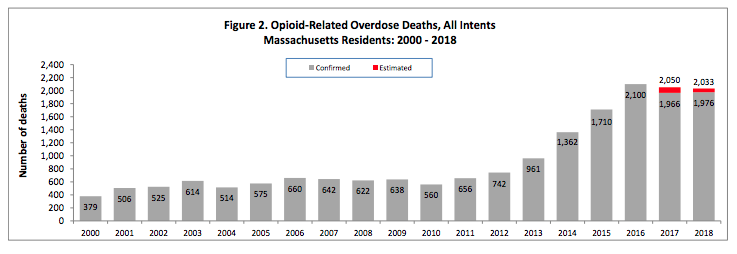

Massachusetts has an opioid death rate around twice as high as the national average, and last year Bristol County was the worst-hit in the state.

These sobering statistics are all too familiar in an unrelenting opioid crisis — and even Dartmouth has not emerged unscathed, with four overdose deaths just last year.

In the Town’s 2018 Annual Report, Police Chief Brian Levesque noted the four deaths occurred out of 64 overdoses in the community.

This means that police and other first responders saved 60 lives in Dartmouth last year alone — in part because they now carry Naloxone nasal spray, which blocks opioid receptors, reversing the effects of an overdose.

But how do we prevent people from setting down the path to an overdose in the first place?

Dartmouth’s Addiction Treatment Centers

Care workers at the town’s addiction treatment centers are fighting on the front lines every day to help individuals struggling with opioid addiction.

“We can’t keep up with the demand,” said Patricia Mitrokostas, Director of PR for non-profit treatment center Gosnold, which has an outpatient center on Faunce Corner Road.

She noted that although deaths in the state are down slightly — a fact she attributed to the widespread use of Naloxone — opioid use rates are “the same if not higher.”

Opioid-related overdose deaths in MA 2000-2018, from MA Dept. of Public Health

Gosnold and other addiction treatment centers specialize in prevention, treatment, and recovery from substance use — mostly alcohol and opioids — as well as any underlying mental health disorders.

Mary Cochrane, Program Director at Dartmouth’s AdCare outpatient center, stressed the importance of holistic care.

According to Cochrane, treatment is more likely to work if it is tailored to each individual’s situation, and includes family and friends as part of the process.

“The family can sometimes get neglected in all of this,” Cochrane noted, adding that family support can be key to recovery, and that an addict’s loved ones “go through a lot” as well.

A silver lining

Representatives from AdCare and Gosnold both pointed out one positive to come out of the crisis.

With so many people affected by opioid addiction, they said, the stigma surrounding addiction is slowly disappearing, and the number of high-quality recovery services is increasing.

“There is a shift in perception of who users are,” Mitrokostas explained. “The crisis is in mainstream America — it’s not just poor neighborhoods anymore.”

“Years ago people were two steps away [from addicts],” she added. “Now they’re one degree away.”

Cochrane herself got into the field due to a family member with an addiction.

She noted that addiction issues are “more open” now, which she sees as positive.

“I think when someone hears that someone is an addict or an alcoholic, it comes as a certain image in mind,” Cochrane said. “And now we’ve come to see that the face of addiction is very diverse.”

Addiction as a disease

Addiction is now understood by medical professionals — and more and more of the general population — as a disease of the brain.

Even short periods of opioid use, such as those prescribed by doctors, can change the structure of neurons in the brain so that people become physically dependent.

One type of treatment plan is to provide a substitute medication — usually methadone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone, which are thought to be safer and don’t get the user high — to replace more dangerous drugs like heroin and fentanyl.

Outpatient services like the ones in Dartmouth, however, focus more on the support and counseling necessary to keep people in recovery.

Adcare Community Services Representative Micaela Kennedy noted that AdCare’s programs include many different types of support groups, including two new ones focused on building healthy relationships and information about cannabis.

The Dartmouth Police Department are also getting involved.

Sergeant Joe Rapoza helps run the department’s Opioid Outreach program, part of a joint effort by Greater New Bedford area police departments to reach out to opioid overdose victims and help get them treatment.

Rapoza said that the majority of overdoses in Dartmouth are not town residents, but those who are get a visit from the team, who work with the Seven Hills Foundation to provide overdose victims with addiction treatment services.

Although Rapoza mostly works behind the scenes in an organizational capacity, he has also witnessed the crisis first-hand.

“I’ve seen people well beyond rock bottom. They’re beneath the rock,” he said. “It’s a very sad thing to watch.”

Rapoza also noted that the number of overdoses in Dartmouth is increasing. “And those are just the ones we know about,” he added.

It is a multi-faceted and insidious problem.

“It’s not just the behavior of using,” Cochrane said. “It’s the whole thought process that led to that, that has to be changed as someone stops using.”

“We try to work with people where they’re at, and refer them to where they need,” she continued — whether that’s helping them sign up for food stamps or referring them to other services.

Both Cochrane and Kennedy said that the work can take a toll.

But for them, it’s worth it.

Said Kennedy, “I think for all those hurdles that you have, and all the sad things that you see, it’s seeing somebody succeed, that’s — even if it’s one in 25, just seeing that, it’s like ‘This is why we do what we do.’”