Not-so-small talk: Residents learn about extreme weather on Mount Washington

Can you believe all of this rain we’re having?

Normally, talking about the weather is reserved for uncomfortable office birthdays, running into an acquaintance at the grocery store, or that awkward moment before the gas station clerk hands you the receipt.

But for more than 60 people attending the Friends of the Dartmouth Libraries’ April 15 virtual presentation on the extreme conditions atop Mount Washington, weather was the main focus.

Director of Science and Education at the Mount Washington Observatory Brian Fitzgerald led the presentation, which touched on the observatory’s history, scientific instruments, climate change, and why the spot is known as the ‘Home of the World’s Worst Weather.’

It’s a combination of very strong winds — the station is home to a world-record 231mph gust measured in 1934, a record held until 1996 — along with freezing temperatures and lots of precipitation and fog that have earned Mount Washington the epithet, according to Fitzgerald.

“In some ways it’s kind of a joke,” he said. “How do you really determine that? It’s a pretty subjective statement.”

“Certainly there are colder places, maybe there are some windier places...wetter places definitely,” he added. “But it’s the combination of those three things.”

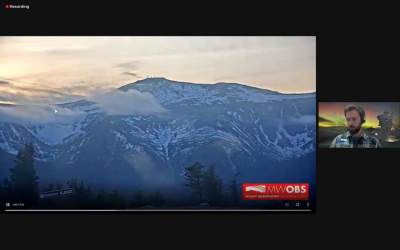

The mountain sticks up alone at a height of 6,288 feet, the tallest peak in the northeastern US, with nothing to block the prevailing westerly winds except lower mountains that act as a sort of wind funnel.

It also gets a lot of storms.

According to Fitzgerald, nearly all low pressure systems in the contiguous US end up tracking through New England.

“This is sort of the tailpipe of America here,” he added. “We are going to see just about every weather event.”

And lightning storms on the mountain can be “exciting and terrifying,” he told attendees, with St. Elmo’s fire streaming off of instruments and towers and lightning striking so close that observers can’t even hear the thunder — they just see a flash and hear what Fitgerald described as rattling tin foil.

The observatory is a nonprofit institution that was founded in 1932 and houses six full time employees, who work with support staff to observe the weather 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

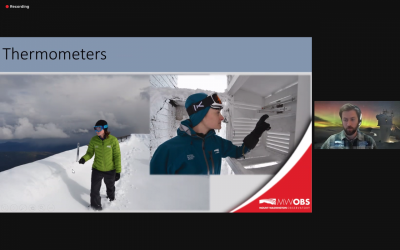

Staffers measure, record and forecast weather conditions like humidity, wind speed, and precipitation, conduct research and education outreach, and test products.

They still use glass thermometers filled with mercury and alcohol for consistency’s sake, noted Fitzgerald.

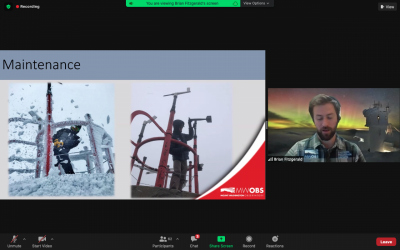

One of the biggest challenges is keeping everything free of ice.

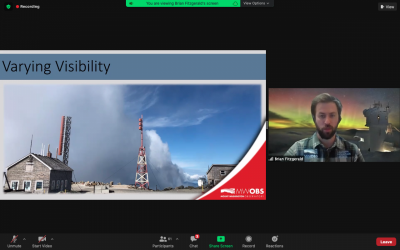

With average annual temperatures below freezing and fog around 60% of the year, rime ice often forms on sensitive instruments, which have to be heated — and can still ice up anyway.

But even on Mount Washington, climate change is making itself felt.

“Mount Washington is warming — but more slowly compared to other locations in New England, including right down at the bottom of the mountain,” Fitzgerald said, adding that scientists still don’t quite know why.

Rising temperatures may impact the mountain’s unique alpine or tundra climate.

Dandelions are already moving into higher and higher altitudes, and more frequent thaws and a shorter winter are likely to continue affecting the plants and wildlife, according to Fitzgerald.

But one rare plant, the Robbins’ cinquefoil, which is not found anywhere else on Earth — just Mount Washington and the higher parts of nearby Franconia Notch — has made a comeback.

After diverting the Appalachian Trail to avoid the areas the plant can be found, the species was taken off the endangered list in 2002.

Fitzgerald answered a dozen or so questions from attendees, who asked about everything from the Northern Lights to acid rain to transportation up the mountain (they use a big tracked vehicle called a snowcat).

He said that observers on the mountain are currently conducting a handful of new projects, including building a new research database and assessing long-term visibility data going back to 1943, among other activities.

But whatever else they are doing, they are probably also talking about the weather.