Prehistory, preserved: Archaeologist gives lecture on local sites

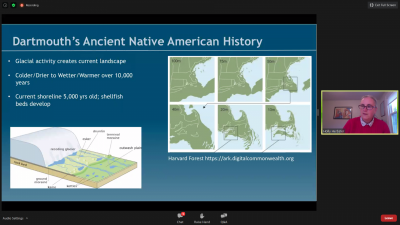

Did you know that the first people in Southeast Massachusetts may have arrived 12,000-10,000 years ago?

Nearly 100 people learned this and other fascinating tidbits during a virtual talk detailing Dartmouth’s archaeological prehistory and history by local archaeologist Holly Herbster on Tuesday evening.

“Native people have lived on this land over millennia and continue [to do so],” Herbster — a senior archaeologist with the cultural resource management firm Public Archaeology Laboratory, Inc. — noted at the start of the online event.

But she said that due to New England’s acidic soil, organic materials like bone, leather, and plant matter from thousands of years ago don’t preserve well — and since ancient coastlines are now located under the sea, many older sites could be located offshore.

“Really really old sites can be really hard to find,” Herbster said. “But I’m sure they exist.”

The talk, sponsored by the Friends of the Dartmouth Libraries, delved into the importance of preserving and understanding our local cultural heritage.

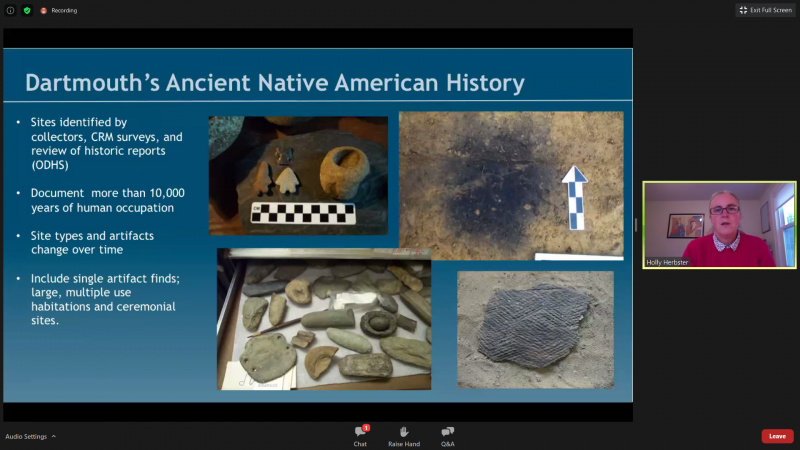

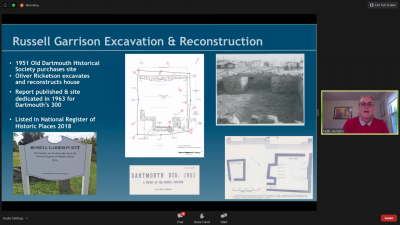

Herbster introduced attendees to the study of archaeology as well as Dartmouth’s own prehistory before honing in on specific historical events and sites such as the Russell Garrison, an archaeological site in Padanaram that was occupied during King Philip’s War.

King Philip’s War was a 17th century conflict in New England that saw more than 2,500 colonists and at least twice that number of native people killed, according to historian Robert Cray, Jr.

Given the population at the time, the conflict is “still today the most deadly conflict that occurred on American soil,” Herbster said. “It was an incredibly violent and traumatic event.”

She also touched on a town-wide, year-long archaeological survey that was undertaken by the town of Dartmouth and the Massachusetts Historical Commission that documented more than 50 archaeological sites not previously recorded.

Although the state’s historical commission has a list of all known archaeological sites, Herbster noted, the information is not available to the general public in order to protect the sites from people who may do harm while hunting for artefacts.

Following the lecture, attendees asked questions about legal protections for sites being developed, what to do if you stumble on bones, artefacts, or ruins, and more.

“If you uncover what you think may be or what appears to be human skeletal remains of any kind, there is a state law that requires you to stop and notify somebody — the police, or whomever,” Herbert said. “Anyone who knowingly disturbs a burial ground or burial site can be subject to criminal proceedings.”

If you stumble on what appears to be an archaeological site while hiking, she added, “Take photos of what you see in the woods, and try and as accurately as possible note the location of it” before getting in touch with the Dartmouth or the Massachusetts Historical Commission.

Herbert finished the talk by noting that the study of archaeology is constantly changing. “We are learning new things all the time,” she stressed.

As for the online lecture experience, she said, “I hope that everyone participates in more of these virtual events, because I’m doing a lot of them now, and I’m finding them to be fascinating.”

A recording of the event is available at tinyurl.com/FODL-ArchVideo.