Reinventing physics: College courses during Covid

Since the campus went largely virtual due to the Covid-19 pandemic last spring, faculty from the Physics Department at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth have been reinventing the way physics is taught at the college.

Fortunately for students, physics professors have committed themselves to providing the same education to students virtually that they would provide in person.

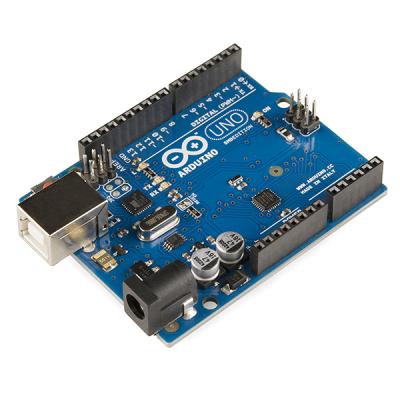

Prof. Alan Hirshfeld, for instance, redesigned one of his laboratory courses around a microcontroller based on the open source platform Arduino.

“I got one and played around with it. It turns out that you can make a viable instructional laboratory course that a student can actually do at home,” he said.

Hirshfeld normally teaches a course on electronic devices and circuits, which focuses on the design and creation of circuits that demonstrates the physics of electricity.

It requires equipment students don’t have access to at home and makes extensive use of class-based troubleshooting techniques.

Transferring this tactile experience online has been “quite an education for a veteran instructor like me,” said Hirshfeld, who has been teaching physics since 1978.

Eventually Hirshfeld discovered Arduino, an educational prototyping system that allows the creation of electronics based on a programmable microcontroller — “And it would only cost students $35,” he said.

Hirshfeld says that after assessing the value of this style of Arduino he “put together a curriculum based on this microcontroller” and has been using the platform since, reporting success in both what students have produced and the knowledge Hirshfeld feels students have retained.

“Students could complete one project, tear it apart and move on,” he noted.

Hirshfeld also shared his plans to repurpose sensors from smartphones using an education program called PhyPhox to collect data about gravity, light, acceleration, rotation, atmospheric pressure and geomagnetic fields — data that smartphones are constantly collecting.

Under the new model, students complete the labs using online simulation software like the modules offered on the Physics Aviary, a resource shared by Hirshfeld, which offers a larger range of experiments than what is normally provided in the span of a semester-length course.

Other faculty members have been forced to make adjustments and have developed methods they also plan to carry into the future.

Prof. David Kagan said he doesn’t “intend to go back to a traditional mode of just lecturing,” a sentiment his colleagues share.

Kagan normally teaches introductory level physics courses which often have sections of up to 90 students.

Knowing that he wouldn’t be able to keep tabs on that many students throughout a class session on Zoom, Kagan instead divided the course into smaller sections that meet once a week, a decision that worked better for students.

“Students are expected to read passages in the textbooks, do problems, then come to class and discuss the material,” he said, noting that he had been considering this type of model even before the pandemic.

This style of teaching has allowed Kagan to develop an assessment of student understanding and retention that makes adjustments easier.

Kagan noted that during a summer course — run as a trial for the fall semester — student retention “didn't seem to be damaged.”

He added that “It was a lot of fun teaching the summer class because we had some really fun conversations that don’t usually happen during a normal physics class.”

Zoom encourages participation, a sentiment fellow physics faculty members Prof. Robert Fisher and Hirshfeld agreed it had been hugely beneficial for measuring student progress in their own classes.

Kagan and his fellow physics professors have spent this year designing a semester-length curriculum that he says must be taught “slower.”

He isn’t talking about the kind of speed that forces students to rush through notes; he references the “judiciously chosen material, in terms of what students should really come out of this course knowing.”

Many physics courses have lab components which demonstrate concepts discussed in lecture compare to Hirshfeld’s course, which is designed to be mostly lab work.

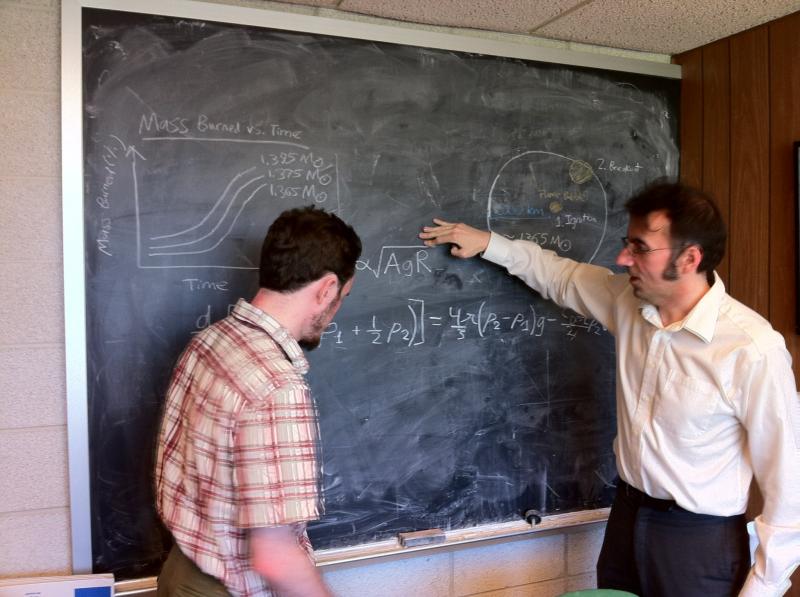

Fisher says that in a traditional lab setting, students interact with teaching assistants who closely oversee the setup of experiments designed to demonstrate concepts covered in lecture.

“Students would have to back off two meters, the TA would have to explain it, make adjustments, mess with the setup to get it right and then sanitize the whole thing,” said Fisher.

Those labs never took place.

Although Hirshfeld’s electronics course is a higher-level course for physics majors only, both Fisher and Kagan were optimistic about translating the level of student involvement in the learning process to introductory level courses.