Shell-tering and shell-ebrating the horseshoe crab

Horseshoe crabs must be in a good mood because according to Sara Grady, a senior coastal ecologist at Mass Audubon, they’re not all that crabby.

In fact, horseshoe crabs are more closely related to spiders, she said.

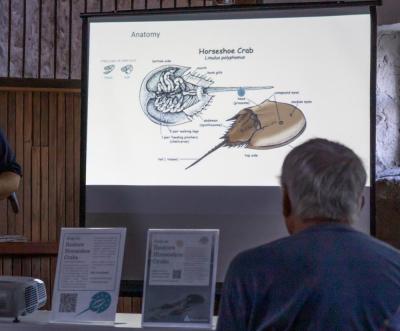

Before working for Mass Audubon, Grady wrote her doctorate dissertation on horseshoe crab population dynamics in Cape Cod, showing off her expertise speaking at the Stone Barn on Thursday, June 27.

In her presentation, Grady clawed into the history of the horseshoe crab and gave warnings for its future.

Horseshoe crabs have been exploited throughout history, and continue to be today, Grady said.

The two biggest recent threats to the horseshoe crab populations are the harvesting of the crab as bait and for biomedical purposes, she said.

Grady said that horseshoe crabs are valuable bait used for whelk fishing, which is responsible for the deaths of 140,000 horseshoe crabs each year.

The crabs are also useful in the biomedical field, she said, because of a special property in their blood that allows it to quickly respond to and form blood clots around bacteria. The blood is harvested from live crabs and then they are returned to the ocean, if they survive.

According to Grady, up to 30% of bled horseshoe crabs die after their blood is harvested.

Despite the threats, as of now, horseshoe crabs might have something to shell-ebrate.

In March, the Massachusetts Marine Fisheries Advisory Commission voted to ban the harvest of horseshoe crabs during spawning season, when the crabs breed and lay their eggs on the shore between April 15 and June 7.

“What’s exciting is that that was one of the things that I said back in 2005 in my dissertation,” Grady said. “So now it’s finally happening.”

Grady said that from what she has heard, the number of crabs spawning on the beach has been higher this year after this change. Although, the full impact of the policy won’t be known for 10 years, she said.

Recent policy changes have been a “massive step” to help recover Massachusetts horseshoe crab populations.

Grady said that the next step to shell-ter the horseshoe crab from harm is to work to ban the harvest of female horseshoe crabs.

“It’s going to take all of us to come up with the solutions and the way we get to a more balanced future for the planet,” said Gina Purtell, Community Science and Coastal Resilience Manager at Mass Audubon.

To end the presentation, Grady gave a claw-some rendition of a sea shanty about the horseshoe crab.

To the tune of “Soon May the Wellerman Come,” Grady sang, “now that these new rules have passed, the spawning crab won’t be harassed and horseshoe crabs in Mass can increase their population.”

.jpg)