Shucking lessons, tasting notes at Cuttyhunk Oyster talk

Did you know that the flavor of an oyster may depend on the time of day it’s harvested?

Or that oyster shells have rings that — much like tree rings — can tell you how old it is and the temperatures of the seasons it lived through?

Dartmouth residents learned these and other tidbits at a presentation by Cuttyhunk Shellfish Farms owner Seth Garfield at the Dartmouth Cultural Center in Padanaram on May 13.

During the talk, Garfield explained his 40-year-old business raising the now famous (and trademarked) Cuttyhunk Oysters before shucking a plateful for all to taste.

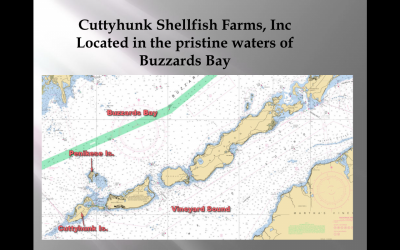

Part of the reason his oysters have become famous is for their crisp, clean, salty flavor, which comes from raising them in Cuttyhunk Island’s West End salt pond.

“We really have no source of pollution,” he said. “And we have daily tidal flow, in a very very unique, pristine pond.”

Garfield wears many hats. He is President of the Massachusetts Aquaculture Association, as well as Cuttyhunk’s Fire Chief, among myriad other duties and interests.

But his main role is running the oyster farm, which he and his wife Dorothy started in 1981.

They buy tiny oysters from a New York hatchery for 10 cents apiece and grow them in suspended Japanese lantern nets until they’re large enough to eat.

Garfield employs local kids of all ages — even college students — for the “endless manual labor” on his farm, which he likened to tending a garden.

“On any given day, I’m sending eight kids out — four are usually harvesting, and four are doing maintenance,” he said, adding that most of them end up working for him for years.

“They basically get paid to be outside, get a tan, socialize with their friends, and do my work,” he joked. When a participant asked if the kids get to eat oysters, he grinned.

“They do,” he answered. “It is an expensive habit.”

And employees also get another perk.

Anyone who works for Garfield gets a free raw bar at their wedding — and, Garfield joked, “if you marry a fellow employee, you can also get shrimp thrown in!”

Garfield’s farm has about 350,000 oysters.

“The nice thing is, they’re a nonperishable product,” he noted. “If you’re harvesting tomatoes, you kind of have this window that you’ve got to get them before they spoil.”

But oysters will just sit and keep growing if unused — which he said came in handy when restaurants shut down during the pandemic.

Garfield said that 90% of the 48 million oysters produced in Massachusetts each year are typically sold in restaurants.

“The whole inventory of oysters is completely backed up,” he noted. “But the oysters aren’t dying...So it’s not as though we’re having to throw them away.”

Participants asked questions and engaged throughout the talk, watching as Garfield showed how to properly shuck an oyster, and slurping them down to taste afterwards.

“Salty,” observed 13-year-old oyster lover Leona Bourland, who paused before adding, “and they have sort of a sweet taste to them.”

Dartmouth resident Barry Griffin said that he moved here from Seattle with his wife three years ago.

“I’ve had oysters all over the world, and I was raised on an oyster farm,” he said. “And these are the best I’ve ever had, these Cuttyhunk ones.”

“They’re delicious,” agreed Mike Santos of Dartmouth, who was interested in learning how to shuck his own molluscs.

“I love oysters, and I love opening them, but I’m not good at it,” he said with a laugh. “Eventually I want to be able to grab an oyster, open it, eat it.”

Cuttyhunk Shellfish does a lot of catering, but also sells oysters directly to restaurants like Little Moss in Padanaram and the Black Whale in New Bedford, as well as to any vessel in Cuttyhunk Pond through the company’s iconic Raw Bar boat.

They now sell clams, shrimp and lobster as well.

But after forty years of farming, Garfield said he is now looking to leave the business in someone else’s hands.

When the kids of the kids who worked on the farm are now old enough to work on the farm, he laughed, “You know it’s time to retire.”