A tern in the spotlight

Terns, the small gray, white, and black birds that flock to Buzzard’s Bay each summer, may seem ordinary to many South Coasters. For Peter Trull, terns are a fascinating, life-long love.

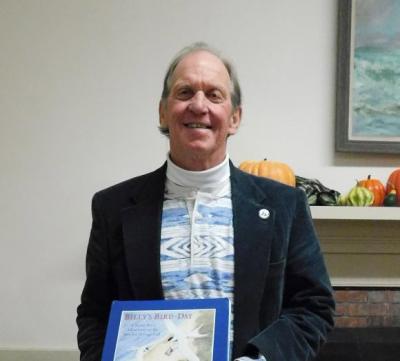

Trull, a naturalist, photographer, and author visited the Paskamansett Bird Club on Nov. 14 to give a lecture on the different types of terns and share photographs from his forthcoming book, “Birds of Paradox: The Life of Terns.”

Trull explained that several types of terns frequent Buzzards Bay: Common terns, Roseate terns, Arctic terns, and Least terns. The common terns, are, of course, the most common.

The distinctions between types of terns are fairly subtle to the untrained eye: Common terns have five black tipped feathers on their wings and a black edge on their tail, while Roseates only have three black tipped feathers and a pure white tail. Common terns have orange beaks, while Roseates have black beaks — that develop orange bases over time.

Roseates get their name from the pink tint of their chests, which is bleached away by the sun within a few days of arriving in Massachusetts from their wintering grounds in South America.

“I am not kidding you when I tell you it took me about 40 years to get an image of a roseate tern showing the pink puff on its breast that gives it its name,” Trull said.

Arctic terns don’t usually nest in Massachusetts anymore, as warming oceans have pushed them farther north.

On Ram Island in Buzzards Bay, an arctic tern and a common tern have been interbreeding for over eleven years. Their young are hybrids, which can also breed, creating new varieties of tern, whchc can be hard to spot.

“And this guy, the Arctic, is going to the Antarctic in the winter, and the Common is going to South America, and yet, they’re still coming right back — it’s a trait called site tenacity — they’re still coming right back to the nest site,” Trull said.

Trull said he saw one tern, identifiable by its band, nest less than 20 inches from where it had nested the previous year, having migrated 11,000 miles to return to almost the exact same spot on the beach.

Terns are known for their large and noisy nesting groups.

Terns catch fish by visually spotting them from the air and diving down to catch them, which they successfully do about one in every six or eight dives. They do especially well when a large school of fish swims by.

Fishing is important not only for a tern’s survival, but also for mating and raising young.

“You’ve got to have a fish if you’re going to find a mate,” said Trull.

Terns show off by catching large fish for potential mates, and, later, bring food for the female while she incubates eggs, before feeding their young an unending supply of fish. Terns specifically catch fish that are proportionate to the size of their chicks — smaller chicks get smaller fish, and larger chicks get larger fish.

For more information about Peter Trull and his previous books, go to www.petertrull.org.

The Bird Club was established 55 years ago, said Club President Lauren Miller-Donnelly. The club initially started as a way for birding enthusiasts to talk about birds they had seen and share tips about good birding spots. Now, it's also a social club for members with monthly meetings and lectures, along with birding walks. To learn more about the Paskamansett Bird Club, go to www.massbird.org/pbc.