UMass Dartmouth archivist outlines the history of Portuguese immigration

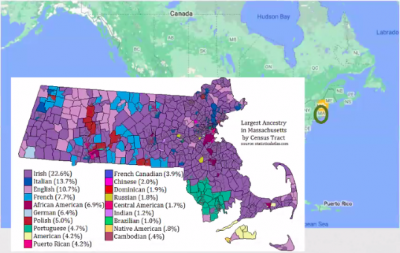

Sousa, Oliveira and Pacheco — these are just a few of the last names commonly found in Dartmouth and much of the South Coast.

How those Portuguese names became common was precisely what the Dartmouth Historical and Arts Society hoped to uncover during a virtual presentation on May 16.

“We all know many friends and relatives from that background,” Society President Bob Harding said. “It’s about time we learn a little more about immigration of the Portuguese people to this area.”

Going over the condensed history was Sonia Pacheco, a librarian archivist at the Ferreira-Mendes Portuguese American Archives at UMass Dartmouth.

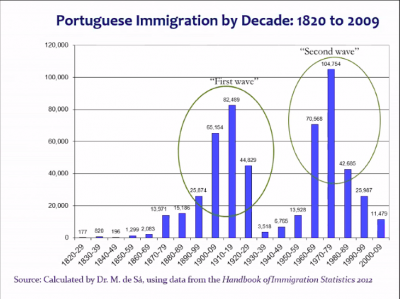

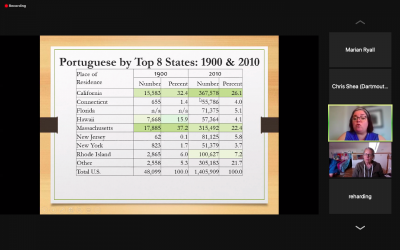

During the presentation, the Portuguese-Canadian went over two of the most significant waves of immigration to the area during the late nineteenth and mid-twentieth centuries.

Pacheco noted that the initial pull toward the South Coast was the fishing and whaling industries in New Bedford.

“Individuals were hired to fish and settle,” she noted. “They actively got on a boat that led them to this area.”

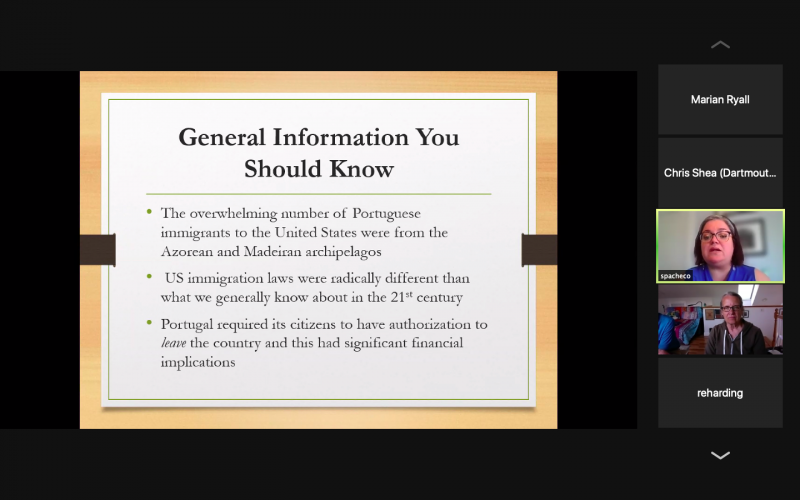

As the industry declined in the 1890s, the bulk of the area’s immigrant population came from the Azores and Madeira archipelagos — mostly to come and work in textiles.

An estimated 218,245 Portuguese individuals migrated during this period.

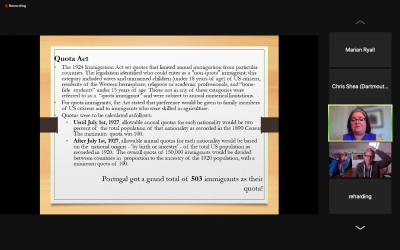

It was with the Immigration Act of 1924 that numbers saw a dramatic halt.

The law set quotas that limited annual immigration from particular countries. In Portugal’s case, that number was 503 immigrants per year.

“It essentially closed off immigration between Portugal and the United States,” Pacheco said.

This continued until the 1957 eruption of the Capelinhos volcano in the Azores.

A year later, then-Massachusetts Sen. John F. Kennedy helped get a law passed in Congress to make an exception in the American immigration law to open the door for thousands of Azorean refugees.

Although the exact number is not known, experts estimate between 2,000 and 5,000 Azorean refugees came to the U.S.

Numbers also picked up with the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 — which abolished the 1920’s quota system. Instead, immigrants were admitted on the basis of their skills and existing family relationships with U.S. citizens.

“They’re now able to reunify their families,” Pacheco said.

This boom would continue in 1974 with the Carnation Revolution — what Pacheco said was identified as a “peaceful coup d'état” that moved Portugal from “essentially a dictatorship to a republic.”

After joining the European Union in the 1980s, immigration to the United States would once again drop as Portuguese people with EU citizenship “had opportunities they had not had” before.

“This was just a very small, quick lesson,” Pacehco said. “Let’s think about this as me combining a semester's-worth of classes into 30 minutes.”