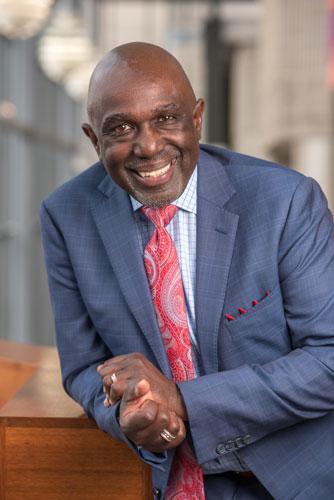

‘I can’t breathe’: Letter from UMass Dartmouth Chancellor Robert Johnson

Dear campus community:

Police harassment and brutality became known to me keenly and personally for the first time as a 13-year old kid growing up in Detroit in the 1970s. As young teenagers, my friend Lindsay and I were hanging out one afternoon, walking down Dexter Avenue from the penny candy store. An unmarked police car pulled up beside us. In it were four white police officers who were known throughout the city as the “Stress Unit.” We called them the “Big Four.”

Multiple units of this force regularly patrolled the city in unmarked cars. This day, they singled us out. Cruising to a stop, they jumped out, grabbed us and threw us against the car hood, pinning our arms behind our backs. Startled and stunned, I repeatedly asked, “What did we do wrong?” One of the policemen who was 6’4” and built like a professional football player snarled, “Shut up, n…word, or else.” Lindsay replied, “Or else what?” I next heard Lindsay cry out with a sharp scream. Then they flung us both to the ground and started back to their car. I shouted, “What did we do wrong?” I can still see the police officer’s smirk as he replied, “We thought you had a knife. Now carry your black ass home.” Once they left, we discovered the officer had broken Lindsay’s arm.

When George Floyd was murdered in Minneapolis a part of me died again. I recalled the story of my father telling me about his youngest brother, my uncle J.C. who was hung from a tree in the Jim Crow south of Birmingham, Alabama. I saw my father, uncles, son, nephews, cousins and most importantly my students within the academy and I am exasperated.

I can’t breathe.

Where else but America can the great-grandson of a slave grow up in the streets of Detroit and become a college president and a university chancellor? Where else but America can my son and daughter have the possibilities of having an abundant life through a strong faith in God, a great education, and the benefit of all tenets associated with the basic concept of freedom? There are many places in the world, even today, where these basic rights do not exist.

But I can’t breathe.

I am an African American male who has served as a college president and university chancellor at two different institutions for 10 years in Massachusetts. My wife and I have a total of six college degrees. But in the context of our criminal justice system, these achievements don’t matter.

At both institutions I have been honored to serve, students of color represented more than 25% and 30% respectively of the student population. Many of them are male. As a father, a son, an uncle, a nephew, a brother, and a university chancellor, I must ask myself, “How do I protect my son and my students in a society where there are fundamental and structural wrongs with how young black men are treated by the criminal justice system? How do I protect my students, whose parents have entrusted their safety and security to me?”

I pray and hope my son or male students do not become a victim of random unfortunate circumstance, simply by being in the wrong place, at the wrong time, with a police officer who may cause him harm. Even at my age, I feel uneasy when a police car pulls up behind me while I am driving anywhere in America — I automatically tense up and experience a moment of fearfulness — even though I have done nothing wrong.

I unequivocally believe that the overwhelming majority of police officers are good, decent people and strive to do the right thing. They also deserve to go home to their families every night. But I can’t breathe because I have a 25-year-old son and African American students growing up in America at a time when some law enforcement officers treat people who look like me differently.

In light of the most recent brutal racist incident with the murder of George Floyd, I had to, once again, sit down with my son and tell him, “Here are some of the things you have to do if you are ever stopped by the police.” While it’s always important to be respectful, I noted that it is necessary to keep both hands visible and if driving on the wheel. I told my son to never do anything that might be interpreted as aggressive: “No matter what the officer says to you, do not talk back,” I advised — because, at that moment, it does not matter if you are right and the officer is wrong. Should he ever be pulled over, I also encouraged my son to pray to God for protection.

It is 2020 more than 40 years after my first encounter with police brutality as a young man, barely past childhood, and I have to now say to my son and my students that you will all too often be seen by some, but not all, police officers as African American first, and a U.S. citizen secondarily. You must assume the worst and hope for the best if you are stopped by the police.

I can’t breathe.

Despite this fact and the other maladies of our criminal justice system and its treatment of African American males, I still believe the United States is the greatest country in the world. We have come through the American Revolution, Civil War, Emancipation Proclamation, Jim Crow, two World Wars, the Civil Rights movement, the Korean and Vietnam wars, Watergate, 9-11, the Great Depression and the Great Recession, and today, a pandemic — and the Republic still stands. I firmly believe America will come through this issue within our criminal justice system as well.

But if we all want to breathe again, so that every American can, in the words of Martin Luther King, Jr., “live in a nation where we will not be judged by the color of our skin but by the content of our character,” then we as a community of learners must not allow racism or bigotry to be tolerated on our campus or any place in the academy, or in our communities and in the nation.

At UMass Dartmouth let us come together and listen to the better angels and not allow the intolerant behavior of a few to stamp out or drown the possibilities of healing a world in distress. I call on all of us to be a voice of one for justice, freedom, and equality for all.

Most importantly, let us begin by first acknowledging the reality of racism in our community and ensure our campus is a place where everyone is welcome and treated as first class citizens and not marginalized simply because of the color of their skin. As a community of learners encourage everyone to strike down racism and bigotry in both public and private domains. When we can heed the words of Edmund Burke — “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men (and women) to do nothing” — then we can breathe again.

UMass Dartmouth, I really want to breathe. Don’t you?

Robert E. Johnson PhD

Chancellor, UMass Dartmouth