Everything you need to know about the Powassan virus and tick prevention

With nearly every type of tick-transmitted disease reported in Dartmouth and the new Powassan virus becoming a threat this year, Dartmouth health officials are imploring residents to be vigilant in preventing bites.

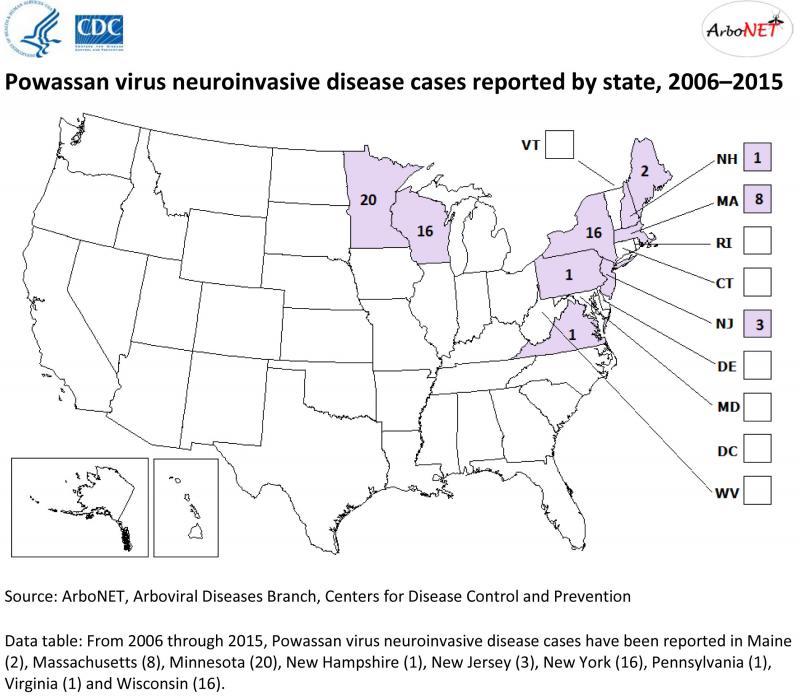

The Powassan virus is rarer than Lyme disease, said Public Health Nurse Erica Hanks, although eight cases of Powassan have been reported in Massachusetts since 2006, according to the Center for Disease Control. It can lead to meningitis (an infection of the tissue that surrounds the brain and spinal cord) and encephalitis (inflammation and swelling of the brain), Hanks said.

“This is probably the most life-threatening. You start messing with your brain and spinal cord…,” said Hanks. Ten percent of cases result in death, while other cases have lead to long-term health problems, she said.

"Some people never feel ill from it. It's like Russian Roulette," said Hanks.

Powassan symptoms — which can include fever, headache, weakness, vomiting, confusion, loss of coordination, speech difficulties, and seizures — can occur between one week and one month after being bit, she said.

“There’s no specific treatment for it,” said Hanks. She listed fluids, rest, and supportive care as musts following an infection.

Unlike Lyme Disease, which can take 24 hours to be transmitted, Powassan can be passed by the tick to the host within 15 minutes. Both are transmitted by deer ticks.

Lyme Disease symptoms include fever, joint and muscle pains, headaches, chills, fatigue, swollen lymph nodes, and an expanding circular rash (like a red bullseye), according to the CDC.

“You don’t have to get the bullseye rash to get Lyme Disease. It doesn’t even have to appear where you were bitten,” said Health Department Director Chris Michaud. He added that a rash could even be a reaction to another bite, such as those from the poisonous brown recluse spider.

Lyme Disease symptom onset can take one week to 30 days, but it can be treated if caught early. If left untreated, Lyme can lead to meningitis and Bell’s Palsy, said Hanks.

There were 3,830 confirmed cases of Lyme Disease in Massachusetts — and another 1,770 probable cases of it — in 2014, according to the state Department of Public Health. Bristol County had the third highest number of confirmed cases, with 479 reports in 2014. Middlesex County had 748, while Plymouth County had 554 confirmed cases in 2014.

Alongside Powassan and Lyme Disease, deer ticks can also transmit babesiosis, or microscopic parasites that infect red blood cells and can cause hemolytic anemia in severe cases, and anaplasmosis, which is caused by bacteria and can lead to difficulty breathing, hemorrhage, renal failure, or neurological problems in the most severe cases.

“I think we’re going to have more of an issue with [ticks] than the mosquitos,” said Hanks.

Dartmouth has three different types of tick species — deer ticks, American dog ticks, and Lone Star ticks, said Michaud. Dog ticks carry Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, which has been reported in Dartmouth within the past 10 years, said Michaud. RMSF symptoms include rash, muscle pain, and vomiting, according to the CDC.

Prevention.

Prevention includes using bug sprays with DEET, and treating your clothes with Permethrin, but make sure you follow the product's instructions. Permethrin should never be sprayed directly on skin, as it is an insecticide that is considered likely carcinogenic by the Environmental Protection Agency.

You also want to wear light colors and long sleeves when in woodsy areas and tall grasses, said Hanks.

“Tuck your pants into your socks. I know it looks silly, but so your skin is not exposed,” she said.

Ticks latch in hard-to-see areas, such as the back of the knee, underarm, base of your scalp, and groin area. Michaud recommended investing in a small, cheap mirror and doing a thorough tick check as soon as you return from the woods, that night, the next morning, and the following night because ticks can be so elusive.

Baby deer ticks — called nymphs — are the size of poppy seeds, while full-grown adults are the size of sesame seeds, said Hanks.

“You really can’t avoid it. It’s checking yourself and being aware. You should be checking yourself anyways for moles, etcetera, ” said Hanks.

Michaud said that it is important to wash and dry clothes as soon as you return from the woods, and to take a shower to rinse potential ticks off of you.

“You want to make sure you limit the opportunity for ticks to establish themselves in your home,” said Michaud. He explained that even if a tick has not latched onto your skin, it can migrate from your clothes and pets. Check pets, children, and clothing thoroughly, he said.

Removal.

To remove a tick, the DPH recommends using a pair of fine point tweezers to grip the tick as close to the skin as possible and pull straight out with steady pressure. You want to make sure you’ve got the tick’s head, said Michaud. Partial removal can allow disease transmission to still occur, or you can get an infection from a foreign body being under your skin, he said.

Once removed, trap the tick in tape, put it in a Ziplock, and refrigerate it. That way, it can be sent to a lab and tested if needed, said Michaud.

Michaud also recommended marking tick activity on a calendar, just in case. For example, if you removed a tick on June 1 and you start experiencing flu-like symptoms six to 10 weeks later, you will be able to provide your physician with helpful information that could aid diagnosis, he said.

If you cannot remove the tick entirely, Michaud suggested going to a physician. As ticks only burry into the skin’s surface, a doctor will be able to safely remove it with a small cut. Don’t worry: Michaud said it won’t hurt, and there’s no scarring.

According to lore, you can smother a tick with vaseline and force it to eject itself from your body. While this may be true, you can also force the tick to prematurely regurgitate any infectious contents into your skin. For example, a tick could transmit Lyme Disease within a few hours if you smother it, while it would ordinarily take about 24 hours, said Michaud. Avoid using vaseline or fire to remove a tick.

Mosquito spraying may not help with ticks, but it can help combat mosquito-transmitted diseases such as EEE, West Nile virus, and Zika. Zika is not yet established in Massachusetts, said Michaud.

He recommended you get a professional to spray your yard, as professionals have to adhere to the labeling and they’re aware of coverage, where homeowners tend to overdo it.

Hanks will discuss Lyme and other tick-transmitted diseases at the Council on Aging on May 26 at 10 a.m. The CoA is located at 628 Dartmouth Street.

Video courtesy: Massachusetts Department of Public Health