Inside the EPA's Bliss Corner cleanup

Old tires. A rusted Texaco sign. Intact milk and whiskey bottles dating back to the 1950s.

These are just a few of the items restoration crews have unearthed during the initial stages of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s effort to clean up Bliss Corner.

“A lot of stuff you’d find in your typical dumps,” EPA project lead John McKeown said.

While that old waste has been easy to identify, it’s what is less visible that the EPA is most concerned with: the prevalence of toxic materials such as lead and polychlorinated biphenyls — also known as PCBs.

The contaminants were first identified in the South Dartmouth neighborhood during the demolition and replacement of a single-family home on McCabe Street in 2018.

Following years of investigation and testing from both state and federal agencies, the EPA approved a plan to remove the contaminated soil from five properties which exceeded the agency’s “removal management level.”

To aid their identification efforts, crews have made use of a mobile laboratory that was temporarily set up outside the former police station on Russells Mills Road — the only such lab in all of New England.

“It’s a tremendous asset — always in demand,” McKeown said.

The lab was primarily used to study samples taken from 19 Kraseman St., which was found to have contamination levels which exceeded the federal safety standard for PCBs — a material that was banned from use in 1979 after the federal government found the substance causes cancer.

How those materials entered the soil is currently the subject of a dispute between the town and the state, but records from the 1950s show Dartmouth officials permitted the City of New Bedford to dump waste onto private properties in Bliss Corner.

Having a lab on-site, McKewon said, allows crews to get information as quickly as possible so they can better know where to excavate on the Kraseman Street site.

“If it's below [the federal standard], then we’re done digging in that direction,” he said. “If it isn't, we'll dig a little more.”

Scott Clifford, the senior chemist who operates the lab, said if those samples had to be sent to the regional lab in North Chelmsford, it could take much longer to get results.

“You could be waiting for weeks,” he said. “I can get results for up to 50 samples per day here.”

To rapidly test PCB levels from the Kraseman Street property, Clifford prepares samples with water to then inject into a gas chromatograph — a device used to separate the constituents of a volatile substance.

Following insertion, samples are passed through a column heated at 200 degrees centigrade in order to remove less volatile materials. The column is then inserted into a detector which responds to the chemical components.

Once the results are printed, Clifford compares the peak readings to the federal standard.

“It’s a lot of steps,” McKeown said.

Each PCB sample takes around 10 minutes to be tested. Approximately 10% are sent to the North Chelmsford lab to affirm those results, which usually confirms his findings.

“If you have a nice, homogenized sample, you’re going to get the same results,” Clifford said.

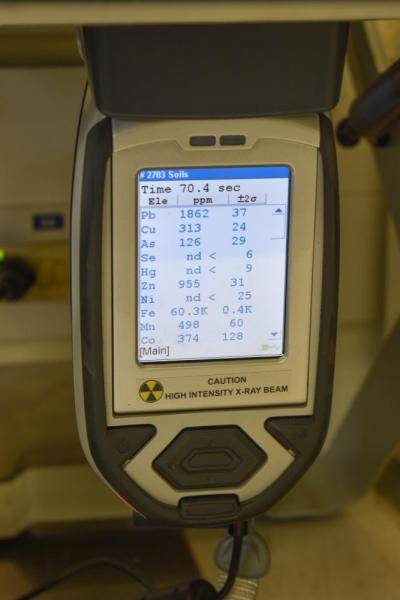

Lead, meanwhile, is a near-instantaneous test.

Clifford uses an X-ray which hits a sample with radiation and excites the electrons of metals. Each identified metal and its levels then appear on a computerized device in real time.

Often, Clifford said, he runs these machines at the same time in order to boost efficiency for those results.

“All day he’s doing this,” McKeown said. “He’s an incredible asset for [the] EPA.”

So far, McKeown said all tests have confirmed previous findings from those hotspots in Bliss Corner.

“That definitely gave us more confidence,” he said.

With that confirmation, crews were finally able to begin the restoration process at the first home, excavating down to clay in order to refill it with clean soil.

With contaminants identified at the Kraseman street property, McKeown said the other four properties “should be more routine” in their cleanups since the PCB levels are within the federal standard.

“At that point, it’s just digging for lead,” he said.

All contaminated soil is stored in a nearby staging area on McCabe street, separated into piles: One for lead, one for PCBs.

Agents also conduct air monitoring and use engineering controls such as liners and covers to control dust and prevent migration of contaminated soil from the staging area.

The agency is currently finalizing a special landfill where the hazardous earth will be sent, but McKeown assured “it’s going nowhere in Massachusetts.”

“It’s certainly going a long way,” he said.

Cleanup is anticipated to be completed at the five properties in either late summer or early fall.