Local historian chronicles escaped slave's story in the South Coast

Seven years. That’s how long former slave and author Harriet Jacobs hid underneath a porch before she could seek freedom in the North.

According to Dartmouth resident and historian Peggi Medeiros, Jacobs thought that if her slave master believed she had escaped to freedom and that she would not be returning that he would sell her children — but that never happened.

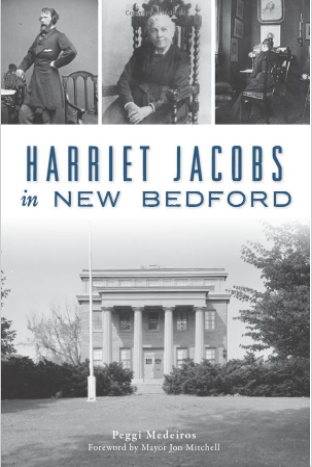

This was just one of many findings Medeiros came across during the research for her second ever book, Harriet Jacobs in New Bedford, which was released earlier this year.

“In a way, this is a study in trauma,” Medeiros said.

In her book, Medeiros chronicles the lives of the Jacobs, Grinnell and Willis families in and out of New Bedford and their bonds throughout such a turbulent period of American history.

When researching, one of the biggest mysteries Medeiros hopes to eventually uncover, she said, is finding out whether Grinnell’s uncle Joseph owned property in Dartmouth.

“I think I found one reference somewhere that indicated that he might have had a farm or something in the town, but I was never able to track it down,” she said. “It’s one of these strange Dartmouth questions — but it was certainly normal for New Bedford families to own Dartmouth farms.”

What inspired Medeiros to do her research was a simple picture. The Dartmouth resident noted that while at the New Bedford Whaling Museum, a friend stumbled across a photo of an African American woman holding a white baby and wondered if it was the famed abolitionist, only for Medeiros to ask “who’s Harriet?”

“That immediately led me on a trek to find out about Harriet Jacobs,” she said. “You don’t often discover that a woman who was as important as Harriet was has a real definite connection to the area.”

Born a slave in North Carolina in 1813, Jacobs lived with her mother as part of a close-knit family — something very rare at that time, Medeiros said. After her mother died in 1819, Jacobs was taken into the home of Margaret Horniblow — the mistress of her freed grandmother.

After Horniblow died in 1829, Jacobs was willed to the Norcom family, where she found herself the object of her master’s sexual advances. While in servitude, Jacobs did from a brief relationship with a white attorney with whom Jacobs had two children, Joseph and Louisa.

Jacobs though that if she were to appear to run away she could make her master to sell her children to their father. To try and fool her slave master, Jacobs hid herself in a crawl under the porch roof of her grandmother's house in the summer of 1835.

“Occasionally, she could come out at night and try to walk around, but it wasn’t easy,” Medeiros said.

After seven years of hiding, she made her escape to the North. For the next ten years, Jacobs lived the tense and uncertain life since under the Fugitive Slave Act, she could have been returned to her master at any time.

During this time, Jacobs met Cornelia Grinnell Willis — the daughter of the prominent New Bedford Grinnell family — while working as nursemaid in Brooklyn.

Medeiros said the two would form a very close bond and visited the South Coast often.

“Cornelia knew if she sent Harriet to New Bedford, she would be safe,” Medeiros said.

In 1852, Grinnell “purchased” Jacobs’ freedom for $50, ending the abolitionist’s fear of recapture. Although, Medeiros said, Jacobs was upset because she felt uncomfortable being bought again.

“But at least she was now safe,” the historian said.

According to Medeiros, for the next few years, Jacobs traveled between New York and Boston, eventually reuniting with her children.

By the start of the Civil War, Jacobs would go on to write her autobiography “Incident in the Life of A Slave Girl” and spent the following years devoting herself to relief efforts in and around Washington, D.C., among former slaves who had become refugees of the war.

“That’s just some of the research I found when doing this book,” Medeiros said. “There just aren’t too many slave stories out there.”