Residents, officials wary over possible septic regulation changes

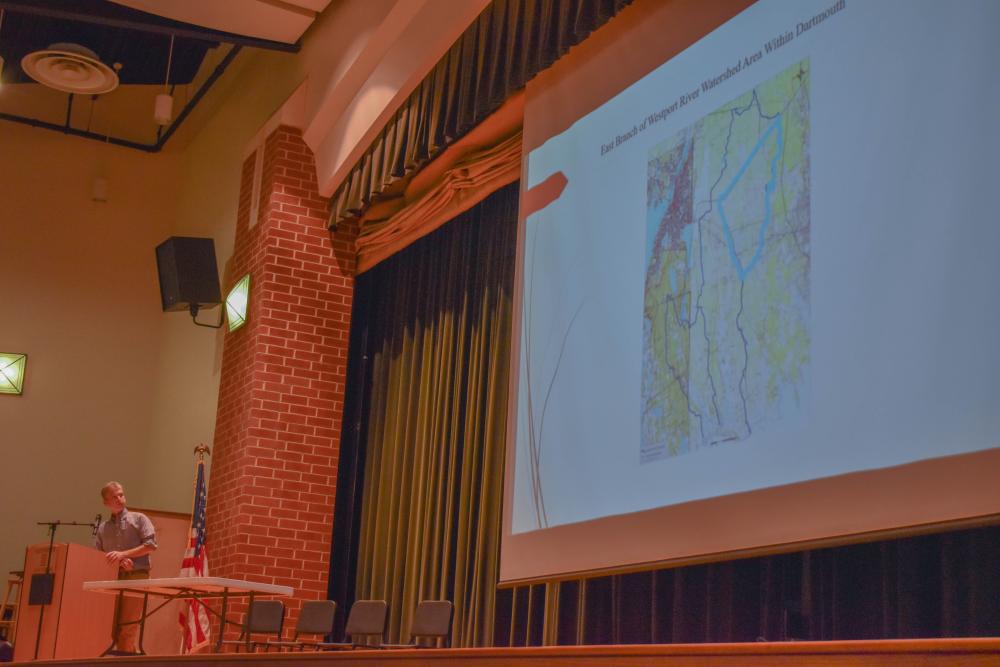

Public Health Director Chris Michaud (left) presents an overview of possible changes to state septic tank regulations on Nov. 16. Photos by: Christopher Shea

Public Health Director Chris Michaud (left) presents an overview of possible changes to state septic tank regulations on Nov. 16. Photos by: Christopher Shea A slide asking what exactly constitutes the technology of the septic tanks residents may have to switch to.

A slide asking what exactly constitutes the technology of the septic tanks residents may have to switch to. State Rep. Chris Markey addresses the audience.

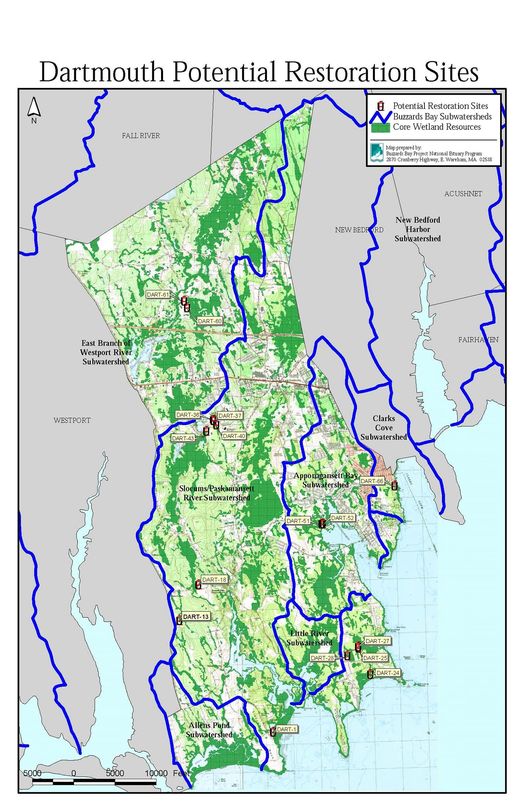

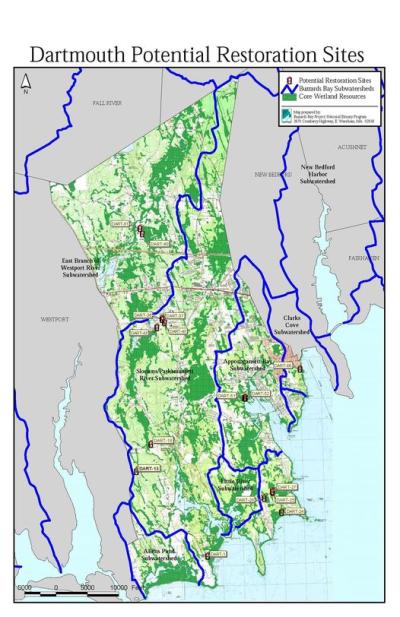

State Rep. Chris Markey addresses the audience. A map of areas where residents could be required to change their septic tanks. Courtesy: Buzzards Bay Coalition

A map of areas where residents could be required to change their septic tanks. Courtesy: Buzzards Bay Coalition Public Health Director Chris Michaud (left) presents an overview of possible changes to state septic tank regulations on Nov. 16. Photos by: Christopher Shea

Public Health Director Chris Michaud (left) presents an overview of possible changes to state septic tank regulations on Nov. 16. Photos by: Christopher Shea A slide asking what exactly constitutes the technology of the septic tanks residents may have to switch to.

A slide asking what exactly constitutes the technology of the septic tanks residents may have to switch to. State Rep. Chris Markey addresses the audience.

State Rep. Chris Markey addresses the audience. A map of areas where residents could be required to change their septic tanks. Courtesy: Buzzards Bay Coalition

A map of areas where residents could be required to change their septic tanks. Courtesy: Buzzards Bay CoalitionA little more than two dozen homeowners came to Dartmouth High Wednesday evening to learn about and raise a stink over proposed changes to state regulations surrounding septic tanks.

Comments were provided as part of an informational session conducted by the Dartmouth Board of Health.

This summer, the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection released a recommendation to update the state’s Title V regulations, which require inspections of septic systems and cesspools before a home is sold or enlarged.

According to the MassDEP, about 2,700 homes connected to septic systems in the Dartmouth watersheds could be affected by the regulation change. Informational sessions such as Wednesday's are held to garner public feedback prior to any official decision by the state.

During the presentation, Dartmouth Public Health Director Health Chris Michaud began with an overview of what led the state to take action: the Massachusetts Estuaries Project.

The project began in the early 2000s and studied 89 estuaries from Cape Cod to Mount Hope Bay in Fall River with the goal of providing state and local officials with the data needed to make good decisions about how to control water contamination.

This study includes two estuaries in Dartmouth: the Slocum River and the eastern branch of the Westport River watershed.

“[And] these are vast watersheds,” Michaud said.

According to the state report, 29% of nitrogen entering the Slocum River is from on-site septic. Other significant contributors include fertilizer, the Russells Mills landfill and atmospheric deposits.

For the Westport River, septic tanks accounted for 34% of total nitrogen pollution.

As a result of the decades-long project, Michaud said the state identified nitrogen from septic systems as a top pollutant, although he contends it is just one of many factors.

Still, the state feels tackling septic systems is the best way to limit the amount of nitrogen flowing into waterways.

One such way is to require all septic systems within watersheds feeding into Buzzards Bay be upgraded to “active nitrogen removal systems” within five years. Residents living in impacted watersheds would also be required to disclose that information if they were to sell their property.

One of the biggest concerns was the price of upgrading. Such systems generally cost between $10,000 to $15,000, according to the Buzzards Bay Coalition.

“To put the burden on homeowners just seems really unfair,” one resident said.

To help alleviate some of that financial burden, the state will allow impacted residents to apply for low-interest loans from their local boards of health for these new systems.

Michaud, though, was skeptical about how helpful the state funds would be.

“That’s not free money; that’s debt,” he said. “Someone needs to borrow the money to install one of these septic systems, [but] the money has to be paid back.”

The public health agent also said the state was unclear on what these new tanks would consist of.

“There is no explicit standard in these regulations,” he said.

According to Buzzards Bay Coalition vice president of clean water advocacy Korrin Petersen, these systems work by transitioning the ammonia found in wastewater to a healthy level of nitrogen gas.

She explained the new tanks first add oxygen to the water to create nitrogen. Oxygen is then moved to a different chamber of the tank to be absorbed by “good bacteria” grown in that environment.

“That turns your nitrogen problem into nitrogen gas,” Petersen said.

The other option the state would provide is for the town to enter into an agreement with communities that share these watersheds to tackle nitrogen pollution independently. Municipalities would have 20 years to reach these goals.

In this case, it would be New Bedford and Westport — municipalities Michaud said have “vastly different” influences.

“I don’t necessarily have a lot of comfort in the watershed permit process as being a recipe for success for our community or any other community,” he said. “To me, it seems like we are setting up our successors to fail.”

Another complaint the public health agent and residents expressed was over Dartmouth allegedly being left out of the state’s decision-making process, with Michaud saying, “they don’t want to listen to me.”

State Rep. Chris Markey (D-Dartmouth), who sat near the back of the auditorium, said while the town may have been left out of things initially, he will be in communication with MassDEP “in a very direct way” with residents' concerns.

“I will strongly be advocating to make sure that these regulations, although well-purposed, may not be the answer to [the state’s] problem,” he said.

Markey also encouraged residents to reach out often as the process continues.

“That’s what’s going to make a difference,” he said, “having a whole bunch of people saying things, not just one or two.”

The state will also host Zoom/in-person sessions in Lakeville on Nov. 30, online Dec. 1, and in Hyannis on Dec. 5. For more information on these hearings, visit town.dartmouth.ma.us/board-health/pages/mass-dep-title-5-revisions.

Affected homeowners can also submit a written comment to MassDEP via email by Friday, Dec. 16. Emails can be sent to dep.talks@mass.gov and must have “Title 5 & Watershed Permit” in the subject line.

All comments submitted must include the name and contact information of the resident.