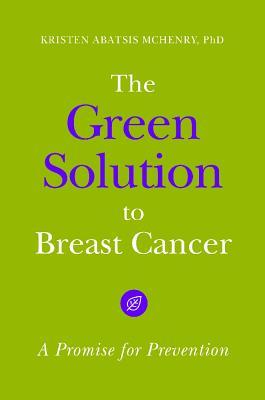

UMass professor moves from breast cancer awareness to prevention in new book

Breast cancer is a cause at the forefront of medical research and social consciousness. But, as UMass Dartmouth faculty member and author Dr. Kristen Abatsis McHenry, PhD found, the number of breast cancer victims is rising.

According to McHenry’s book, “The Green Solution to Breast Cancer: A Promise for Prevention,” the lifetime risk of breast cancer for women has risen from 1 in 20 in 1964 to 1 in 8 today.

“Why are things getting worse, not better, when we know so much more?” McHenry asks.

“The Green Solution” assesses the link between breast cancer and its possible environmental causes as well as social, corporate and gender-related factors.

McHenry asserts that the statistical increase is due to environmental hazards such as pesticides, chemicals like BPA and water contamination and pollution, all which have risen exponentially in the last few decades.

“Proving environmental harm or making any kind of causal claim about what causes cancer is difficult and it’s complicated…. The President’s cancer panel [said] yes, in fact, environment is linked to cancer. We can’t ignore this.”

The book’s beginnings echo McHenry’s Ph. D dissertation on the breast cancer movement in the United States. Over nearly a decade, McHenry examined the rise in rates of breast cancer, the environmental causes behind the rise and breast cancer awareness activism.

“The people I was interacting with at the beginning, some of them are dead now,” McHenry said. “And that’s… a really powerful testament that this disease is killing women, and I think that is why I was struck by women who felt like they didn’t want to be told to smile and wear pink.”

Her book approaches breast cancer from two angles: the “pink movement” that centers on developing awareness of, coping with and managing breast cancer, and the “green movement” which focuses on the environmental causes to try and curb breast cancer rates.

The pink movement is largely “consumer-based activism” centered on awareness rather than prevention, McHenry said. Much of the literature on breast cancer dealt with the “pink” aspect, “which is looking for a cure, awareness, mobilizing women towards this consumer-based activism,” she continued.

“We need to move beyond this conversation about awareness,” McHenry said. “We know about breast cancer, we’re aware of it.”

According to her, the next step in the fight against breast cancer calls for better legislation, including greater transparency among companies, forcing them to disclose if any carcinogens are in their products and more government-initiated research into environmental causes.

McHenry, whose aunt is a breast cancer survivor, and her family regularly attended breast cancer awareness events.

“You go to these events to honor a survivor and… you feel like you’re doing something and that feels really powerful, but what I noticed right away is that after the events… they start giving you frisbees and Nutrigrain bars and Yoplait yogurts and all of this merchandise,” McHenry said. “It becomes this consumer movement… what’s going on here, where is the money going, why is there a consumer-based activism around this disease that affects so many people?”

As individuals, there is only so much one can do to protect themselves from environmental harm. Though people can go out of their way to avoid products with BPA, makeup with “lead in your lipstick, toxic chemicals in your mascara,” much of the change must come from a corporate level, McHenry said.

One of the other most important aspects of her book was identifying how our culture views femininity and how that perception affects the pink movement.

“Why is it that we’re so concerned about breast cancer and not ovarian cancer?” she asks.

Breast cancer awareness has been marketed in a plethora of ways, the most common of them taking a “save the tatas” approach where women’s bodies are sexualized to coerce interest in finding a cure.

“I think that sort of sexual objectification is problematic. I think expecting women to respond to cancer differently than men is problematic,” McHenry explained.

Where women are typically reduced to “tatas” to be saved, campaigns like Livestrong urge men to be “tough” and be “warriors.”

“Companies need to be held accountable for the way that they’re using pink ribbons,” McHenry said.