Round the Bend Farm hosts three-hour composting demo, farm tour

The five attendees at Round the Bend Farm’s worm composting demonstration got to do more than watch worms wiggle with their $10 admission on June 11. Permaculture apprentice Nate Sander introduced guests to the animals, explained worm composting, and even let attendees play with cow poop.

“This is where the compost starts from,” said Sander, fanning out the layers of soil where a pig pen had stood during winter. “Every single day, they’re pooping and getting fresh hay,” said Sander.

The two sows—Georgia and Sandy—feed on whey, a byproduct from a local, organic cheese producer. Their poop piles up in the hay bedding, but the pigs—who like to dig—turn the combo with their snouts. Following a season, the mixture is moved with a bulldozer for a year of decomposition, said Sander.

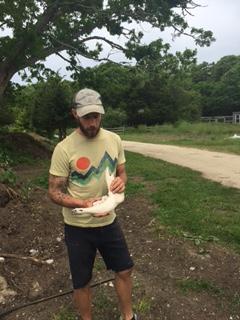

The finished product looks like dirt and has no smell, but may contain a pig’s clean, white jawbone, as it did when Sander led the demo. He explained that post-slaughter, animal blood, bones, and heads usually end up in the compost pile.

“This ecosystem has a way of naturally balancing itself,” said Sander. The compost will feed nutrients to the garden, the animals eat the vegetables and till the hay-poop combo into soil, the animals eventually pass into the land that fed and housed them, and their bodies go into the soil that feeds the plants, he explained.

Next, visitors were led to “the vermiculture hotel,” which was once a greenhouse, but has been reworked to host the farm’s worm population.

“They don’t like cold. They don’t like it super super hot either. They do like the dark,” said Sander.

The worms live in repurposed produce crates, with a removable ceiling, holes in the walls, a gridded, wire floor, and straw, cardboard or leave-based bedding. The farm uses red wigglers because they don’t go further than the ground below the nest. Earthworms tend to migrate, said Sander.

The worms are fed egg shells, coffee grounds, and bananas, and will eat half of their body weight each day. “No dairy. No meat,” Sander warned. “If it smells, you’re not doing it right.”

When the box is full of casting—the dark, rich soil resulting from a worm’s digestion—you stack the full crate on top of one with just bedding and food. Shine a light source over the tower, and the worms will bury down and fall through the wiring into their new home. All that will be left is soil, said Sander.

Sander said it’s easy to try this on a smaller scale. A wood or plastic crate will do, as long as the bottom has openings. Put them in a dark, damp place, like under the bathroom sink, and feed them small bits of kitchen scraps daily. “Find something that fits into your daily routine, and doesn’t stress you out,” suggested Sander.

If everything is done correctly, the whole colony can double in three months.

Leaving the vermiculture shack, Sander talked about cow manure. The best manure comes from a lactating cow—like the farm’s Holstein, Milkshake, whose most recent calf Milkdud was not available for greetings.

A steaming wheel barrel of cow patties greeted guests in their final composting demonstration, which used a recipe from biodynamics expert Maria Thun. It calls for equal parts manure and nettles, accompanied by dried and crushed organic egg shells and basalt.

“In theory, this is like a supervitamin [for plants],” said Sander.

Participant Cindy Azevedo cut nettles while Sander mixed them into the manure with the other guests.

“I’m in the natural health field,” said Azevedo. “As much as we want to empower people in the health system, I think food also empowers people with their health.”

The concoction requires an hour of mixing. Sander left it to dry out, and he will later pour it into a brick-lined pit—which allows for airflow, but keeps water out. Other plants can be added, like dried chamomile, yarrow, and dandelion flowers. Following decomposition (which should be done by fall), the mixture will be diluted in water to form a tea that will be sprayed on approximately 500 plants. The tea helps all parts of the plant—from leaves to roots, said Sander.

As an apprentice, Sander lives on the property in a small hut which he let the group tour afterwards. He also led them through the chicken coops, a wood-cutting area, and the construction site that will become a library, hangout, and education building.

The workshop concluded with Open Farm Day, which included fresh lettuce and radishes at the produce stand, asparagus and sausage samplers, and locally made honeys and syrups.

Round the Bend Farm’s next workshop will be on raw foods. Visit roundthebendfarm.org for more information.