Uncovering the history of Dartmouth’s King Philip’s War garrison

During the King Philip’s War, Dartmouth’s early settlers sought safe haven at a piece of Dartmouth’s past: The Russell Garrison.

Now a recognized national historical landmark, archeologist Holly Herbster led a retelling of the site’s history – and what she uncovered through painstaking research – at a Dartmouth Historical and Arts Society lecture on November 18.

The “garrison” was not actually built as a proper fortified structure. Instead, it was the homestead of John Russell. The well-known Marshfield constable and clerk acquired the property from Myles Standish between 1662 and 1664.

As one of Dartmouth’s early proprietors, he owned a large swath of land from Clarks Cove to the bay. He built his homestead on what was known as the Old Fort Brook, now known as Fort Street. Although not originally built as a safe haven during periods of violence, it soon gained that reputation during the King Philip’s War. It was one of only about 30 homesteads built in Dartmouth at the time.

“There’s no indication the home the Russell family lived in was altered to use as a defensive spot during King Philip’s War, but it was during this period and in colonial records that Russell’s home began to be referred to as ‘The Garrison,’” Herbster said. “That’s where the name comes from.”

In addition to serving as a place of safety for the early residents of Dartmouth during the war, the historical record includes eyewitness accounts of historical events at the garrison.

In July 1675, a group of Native Americans surrendered their weapons and sought refuge at the garrison site. Russell agreed, and offered them Little Island – thought to be land nearby extending into the harbor – as refuge. Later on, they were taken to Plymouth, but considered enemies and sold into servitude. In July 1676, a company of men sought refuge at the garrison following skirmishes in Acushnet.

In her research, Herbster discovered a gap in written records of the garrison from after the King Philip’s War to the early 1800s. Among the important information not yet discovered: When the original homestead was dismantled, as the original structure no longer exists.

The first mention she found on the historical record came from a will deeding a gun supposedly fired from the garrison. According to a story recounted in the will, a colonist fired upon a Native American who made a “rude gesture,” and managed to strike the person despite the large distance and the general inaccuracy of firearms of the time period.

Several newspaper articles were published in the late 19th and early 20th centuries recounting the site’s history, demonstrating the property still lived on in the minds of Dartmouth residents.

In 1951, the rich history of the still completely undeveloped land was put at risk, as a developer proposed to build a subdivision on the site. One Dartmouth resident was up to the challenge of saving the property: Oliver Garrison Ricketson.

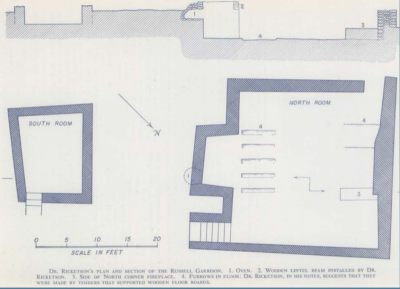

The world-famous archeologist had just returned to South Dartmouth for his retirement, and volunteered to undertake a major archaeological survey and excavation of the property.

Between June and September, he and a crew of three laborers conducted extensive excavations, and produced land and site maps, and produced drawings of what he believed the homestead originally looked like – although not exact, as he relied on existing homes from the era and a book on early colonial architecture to guide his reimagining of the site.

Ricketson’s data led to the reconstruction of the walls of the garrison, which still exist to this day – although they were filled in in the 1980s owing to safety and structural issues, leaving only the tops of the walls visible from the site today. Following the reconstruction, the Old Dartmouth Historical Society acquired the property, and deeded it to the town in 1989.

WIth renewed interest in the property in the early 21st century, the Dartmouth Historical Commission and Herbert worked to recognize the garrison as a national historical landmark. Final approval came in 2018, and the garrison site was officially added to the National Register of Historic Places.

All that’s missing is a sign commemorating the listing, which is due soon.