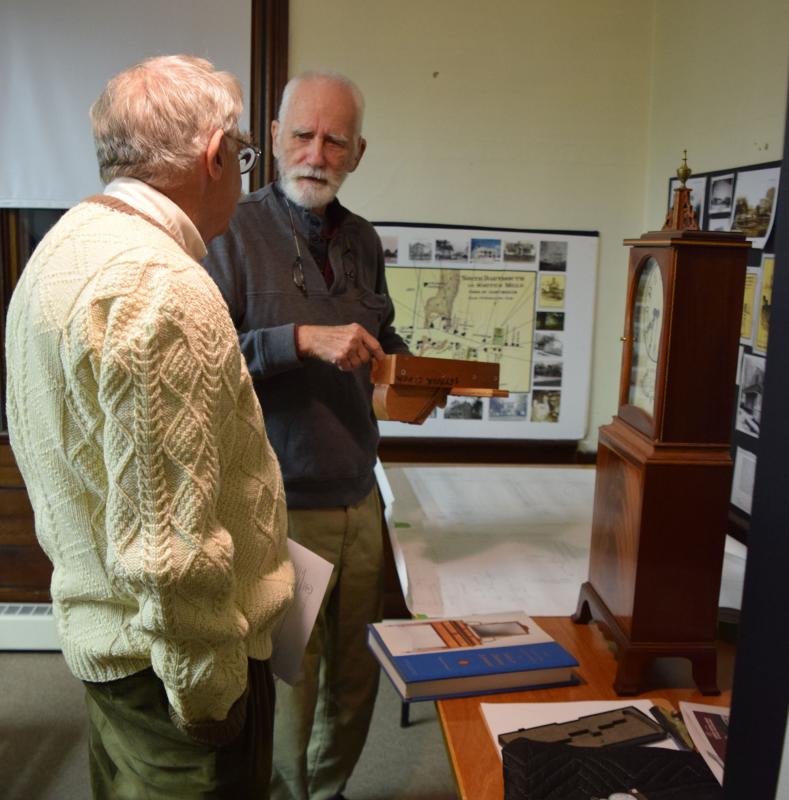

Resident presents hand-built clock at historical society meeting

For Dan Socha, there is something special about clocks. The Dartmouth resident has been building his own hand-crafted clocks for years, and most recently stepped into the world of historical reproduction.

At a Dartmouth Historical and Arts Society meeting on November 20, Socha detailed his first attempt at recreating a 19th century shelf clock originally created by the famed New England clock-making and woodworking families, Willard and Seymour.

Socha’s first exposure to historic clock design was through a book that Gary Adriance, owner of Dartmouth-based Adriance Furniture, had gifted to him.

“He knew I liked clocks, so he introduced me to this book on masterworks,” said Socha, who did subcontracting work for Adriance’s company. “I thought it would be a really great project to build one.”

When Socha found a design in the book that he liked – a shelf clock – he decided to make not one, but three reproductions: one for himself, and two for Adriance Furniture. It began a nearly year-long project that included conducting extensive research into the Willard and Seymour families.

The book Socha received only offered four clues for creating blueprints: the height, width, and depth of the clock, and a single picture of the front. Socha did not know if the drawing was to scale.

Using a dial caliper — a measuring instrument used to calculate outside diameter, length, height, or thickness of a part — Socha confirmed that the photograph was indeed drawn to scale. However, he had no idea what the internals looked like, so he visited The Willard House and Clock Museum in Grafton to get a feel for how Willard designed the internals of his clocks.

“All craftsmen have their own way of building things,” Socha said. “I wanted to look for Seymour’s signature.”

He completed a preliminary design after examining a number of shelf clocks at the museum, but soon ran into what he called “quite the puzzle” after looking closely at the feet that support the clock.

“The grain was vertical, but you don’t make anything with short grain,” Socha said, explaining that the way the clock was shown in the photo would make it prone to splitting under the stress of repeated expansion and contraction.

He soon discovered that Seymour had intentionally used vertical grain on the feet to stay consistent with the grain on the rest of the clock, sacrificing longevity for a consistent look. Since it was Seymour’s design, he made no adjustments, but did add a support system at the base of the clock to prevent damage.

In all, Socha said the most challenging part of his clock adventure was the fret work – crafting the intricate designs for the decorative piece at the very top of the clock. Fret work looks best thin, but Socha risked causing damage if he tried to make the designs as thin as possible.