Hidden treasure awaits Dartmouth's geocachers

A presentation at the Southworth Library offered a tantalizing proposition: if you know where to look, there is treasure hidden all around town.

Geocaching extraordinaire Tyler Clark visited the library on Feb. 13 to discuss the baubles one can unearth around Dartmouth (and around the world) with a little patience and some adequate cellphone reception.

Geocaching, as described by Clark, is “worldwide, high-tech treasure hunt.” The phenomenon started in May 2007 and has grown in popularity ever since.

“A perfect summary of geocaching is using million-dollar satellites to find tupperware in the woods,” said Clark, adding that he was wearing a T-shirt emblazoned a similar phrase.

Players hide boxes – typically tupperware containers – filled with small trinkets and a logbook. These caches can but tucked inside a hollow log or beneath a bridge, for example.

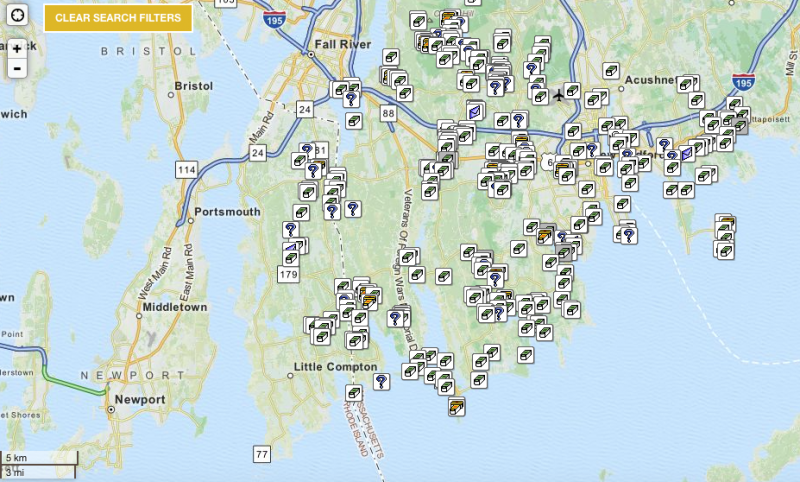

The player then shares the GPS coordinates online, complete with any additional clues. Users can then search the official geocaching website’s database for locations in their general vicinity and go hunting. The coordinates can be punched into a handheld GPS or a smartphone.

“It’s hard to say where geocaches aren’t hidden. Public parks, walking paths, conservation areas, sides of the road, people’s yards and parking lots. After you start geocaching, you will never look at a guard rail the same way again,” said Clark.

For the player's efforts, he or she gets bragging rights online. The website tallies the total number of caches the player has managed to locate. Clark and his family have located more than 6,600.

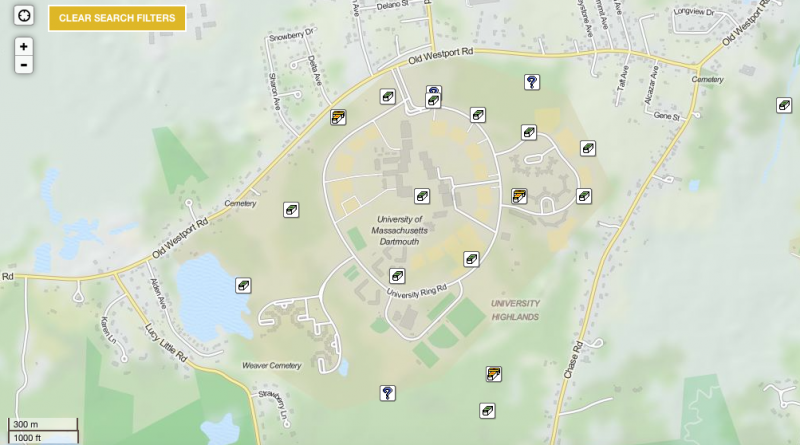

Clark, 24, now a 7th grade teacher in Rhode Island, hid several caches around UMass Dartmouth before he graduated from the university.

For instance, he stashed a cache by the large bell tower in the center of campus. Rather than instructing the user to simply look around the Campanile, Clark’s directives read like a riddle, prompting players to “sit a few feet from the end of the bench in front of the low hanging shrubs,” “face the tower” and “push back the shrubs directly behind the bench and peek in.”

There are several rules to the game. Users should hunt with a pen so they can sign the logbook contained within the container, they should have items to leave inside the cache once locating it and, once refilled, players should put the cache back exactly where they found it.

There are several rules governing where a player can start a cache of their own. Government property and public schools are forbidden. Clark said that Dartmouth Natural Resources Trust has stopped accepting new geocaches on its trail systems as well. The official website has a full list of rules, and new locations need to be approved by reviewers.

While inspecting shrubbery for plastic containers may sound like a bizarre way to spend an afternoon, Clark and the numerous diehard geocachers in attendance at his lecture described the hobby as an obsession. Geocaching won’t make anyone rich – many of hidden treasures amount to nothing more than a plastic action figure or a trading card. But the thrill of the hunt keeps them, as well as 15 million other geocachers across the globe, hooked.

For Dartmouth resident Mike Santos, geocaching was a way to lure his kids away from all-day video game sessions.

While his kids are less active now that they're older, now that he has grandkids, he’s looking forward to taking them outdoors in search of tiny plastic capsules.

“It was way to do something with them, take them outdoors and show them the beauty of nature,” said Santos. “Dartmouth has some beautiful places.”

For those interested in giving geocaching a shot, Clark hid a small container in front of Southworth Library (which you can locate at N 41° 35.970 W 070° 56.483). The name of the mission is called “Hitting the Books.” You can sign up for a free geocaching account at geocaching.com.