Rates of 'high needs' students are on the rise due to state laws and social factors

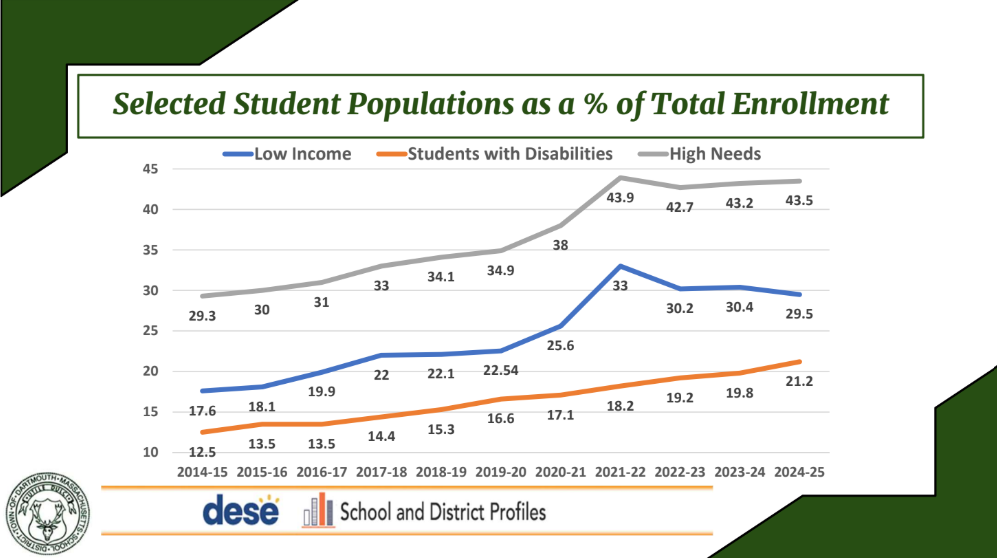

Due to a combination of changing state laws and potential social factors, the rate of high needs students in Dartmouth Public Schools has risen more than 14% in the past 12 years.

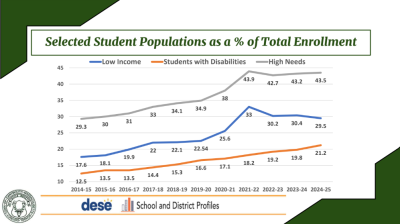

During financial planning, the School Department announced that the rate of high needs students has increased from 29.3% in 2014 to 43.5%.

“I don’t think it’s a matter of something unique to Dartmouth, I think it’s much more reflective of a nationwide trend,” said Ross Thibault, the director of teaching and learning at the secondary level.

“High needs” includes students who are disabled, English Language Learners and students who are low income. Both the percentages of disabled and low income students have increased since 2014, from 12.5% of disabled students to 21.2% and 17.6% of low income students to 29.5%. The rate of English Language Learners in Dartmouth is only 1.7%.

“A high needs student really is a student who needs additional support in some way,” said Superintendent June Saba-Maguire.

Dartmouth is below the state average of about 53% of students being high needs.

Besides the rising unemployment levels and number of people in low-paying jobs, the percentage of low income students has risen because the state passed new laws about how to help students whose families are struggling financially. Before, families would apply for benefits such as the free lunch program, which was how the percentage was calculated previously. Now the percentage is calculated by the state based on SNAP benefits and income levels.

Dartmouth is a Title 1 school based on the percentage of low income students, allowing the district more access to supplemental services.

There is not a known reason for increasing rates of disabled students, although some school officials have their theories.

“It’s a mirror of what’s happening across the state and across the country,” said Catherine Pavao, the executive director of teaching and learning at the elementary level.

A leading theory, both within Dartmouth and nationwide, is the increase in diagnoses of ADHD and ADD and the mental health crisis. The increase in diagnoses is partially because the criteria to be diagnosed expanded in the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, which is a medical book laying out the criteria for diagnosing most neurological and mental disorders.

Another theory is that there are more support systems in place for students who need help and more students requesting these services.

There is also the theory that COVID learning loss created learning gaps, meaning students who were younger during the COVID pandemic are further behind than students who were in school prior to the pandemic.

The last theory mentioned is that school has gotten more rigorous, and students need more support to succeed.

“With what we’re seeing in today’s youth, as far as mental health and attention and sort of that neurodiversity lens, we all need different things to be successful,” said Laurie Dionisio, the executive director of student support services, “I think that that’s the best thing that comes out of it and that we can be a support to each other in that process.”

All public schools in Massachusetts are mandated to have programs that support students with disabilities.

Dartmouth has the ATLAS program, which stands for Advancing Toward Life After School, which is open to students with disabilities ages 18 to 22. This teaches them to function on their own, with lessons on cooking, cleaning and going into the community to learn skills like holiday shopping.

Eighty percent of disabled students in Dartmouth public schools are in co-taught classrooms. In co-taught classrooms, there are two educators who teach a class with both disabled and non-disabled students. Other disabled students are in sub-separate classes, where they spend 60 to 80% of their day in a small and specific classroom, and the rest of their day in a general classroom. Students are in co-taught or sub-separate classrooms depending on what suits their needs.

About 20% of students have IEPs, which provides them with accommodations to succeed like longer test times or separate classrooms for testing.

If the public schools cannot provide a student with the support they need, the school will pay for the student to attend a specialized school.

“It’s really about looking at what we can provide at the setting and seeing the different levels we can pull that might make them successful,” said Dionisio.